What EDI means for science institutions

The statement below, from the Royal Society, the foremost national academy of science, engineering, technology, and mathematics in the UK, created in 1660, exemplifies the perceived reasons for and importance of incorporating EDI values in academic practices and process. The dominant motivating benefits are widening and strengthening of participation in the science enterprise to diversify intellectual and creative capacity of the science workforce:

Diversity is an essential part of the Royal Society’s mission to recognise, promote and support excellence in science, and to encourage the development and use of science for the benefit of humanity. A diverse and inclusive scientific community that brings together the widest range of talents, backgrounds, perspectives, and experiences maximises scientific innovation and creativity, as well as the competitiveness of the UK scientific industry. Yet, the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) sector in this country is not as diverse as it could be as shown in many reports including those commissioned by the Royal Society. We want science education and careers to be open to all and to create a research and innovation sector that is inclusive and welcoming.

Oppositions to EDI in academic institutions

Many universities and funding organisations in North America have experienced intense criticisms of their EDI policies from some academics on the grounds that these policies are used as tools to enforce ideological conformity or limit academic freedom, which jeopardizes both academic rights and the integrity of higher education.

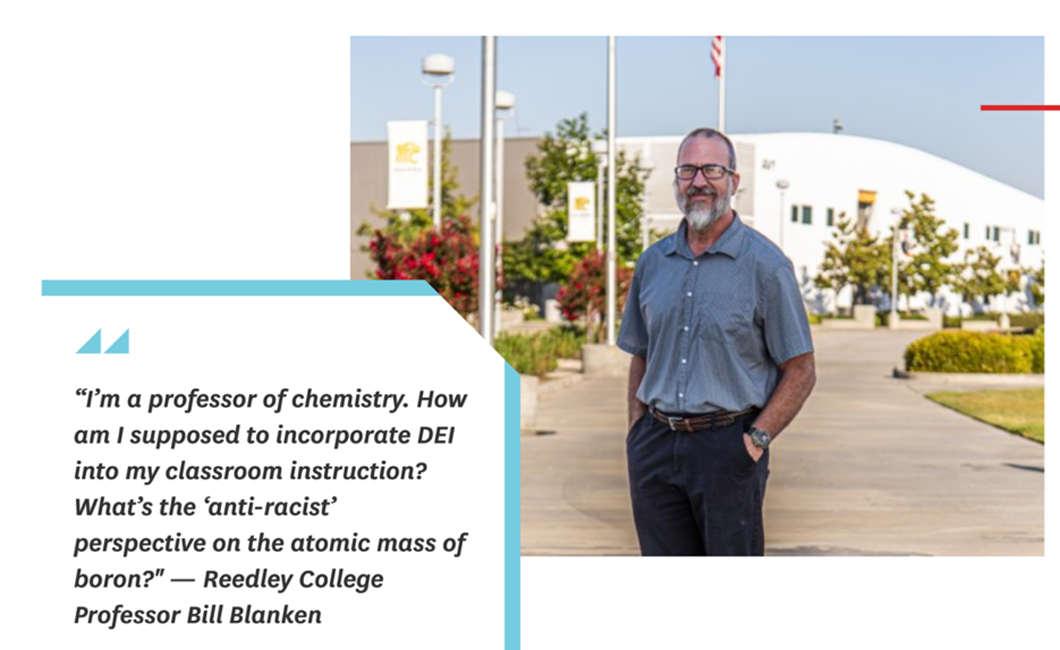

A case of an objection to applying an EDI perspective in the context of academic work is exemplified in the argument made by a professor of chemistry in the USA in relation to his teaching the properties of the chemical element boron.

Clearly, he is right that at the level of its basic physical and chemical properties boron is free from the effects of EDI. However, applications of this knowledge have multiple uses in relation to health where examination of EDI and gender dimensions (sex/gender, age, ethnicity/race, environment etc.) aspects could be very relevant to ensure that the quality and impact are equally good for all potentially benefiting groups. For instance: (1) boron is essential for the growth and maintenance of bone; (2) boron greatly improves wound healing; (3) boron beneficially impacts the body’s use of oestrogen, testosterone, and vitamin D; (4) boron boosts magnesium absorption; (5) boron reduces levels of inflammatory biomarkers; (6) boron raises levels of antioxidant enzymes; (7) boron protects against pesticide-induced oxidative stress and heavy-metal toxicity; (8) boron improves the brains electrical activity, cognitive performance, and short-term memory for elders; (9) boron influences the formation and activity of key biomolecules; (10) boron has demonstrated preventive and therapeutic effects in a number of cancers, such as prostate, cervical, and lung cancers, and multiple and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; and (11) boron may help ameliorate the adverse effects of traditional chemotherapeutic agents.

Politicisation of EDI in Europe

One recent academic study in Sweden questioned the government’s policy to promote gender mainstreaming at Swedish universities by arguing that “gender mainstreaming was introduced as a form of identity politics through government action and de facto supervision; that the latter was problematic from the perspective of institutional autonomy; that the choice of gender studies as a preferred scientific framework for university policy had a chilling effect on inquiry and free speech in other areas of research; and, finally, that gender mainstreaming led to violations of some scholars’ individual rights”.

By contrast to Sweden’s policy efforts to mainstream gender into all publicly funded institutions, the governments in Hungary and Romania have instead confronted the debate on equality, diversity, and inclusion by claiming that gender studies represent ideological rather than scientific purposes and whilst Romania was not successful in the attempts to abolish gender studies in higher education institutions, Hungary has achieved that objective.

EDI as barrier to academic freedom

Some academics object to EDI by saying that EDI prevents academic freedom by limiting “professors’ ability to choose their research and pursue it as they see fit”. Such argumentation will appear as irrational to women scientists in Afghanistan, or LGBTQ scientists in Uganda, or any scientist in North Korea, and, indeed, all scientists in the 100 countries that according to the Academic Freedom Index (AFI), which monitors 179 countries and relies on 2328 experts to assess evidence on freedom to research and teach; freedom of academic exchange and dissemination; institutional autonomy; campus integrity; and freedom of academic and cultural expression, have completely or severely restricted academic freedom.

INSPIRE’s contribution to evidence-based consensus on why EDI is good for science

One of the goals of INSPIRE is to facilitate dialogue between different actors and stakeholders to explore policy pathways incorporating EDI criteria into existing measures of R&I quality and impact. This will be done through three policy workshops and two conferences. The first policy workshop has taken place on 6th October 2023, a day after the first INSPIRE conference. Future policy workshops will be held in 2025. The overall aim is to create consensus among researchers, science leaders and science policy makers on the definitions of EDI values in the context of science knowledge making practices, and to confront through evidence criticisms motivated by privilege or political interests, based on outdated, narrowly conceived criteria of research(er) excellence and quality of research outcomes.

By: Elizabeth Pollitzer, Portia gGmbH